The Keys To Feeding Piglets Without Zinc Oxide

We interviewed Gonzalo González Mateos, Full-time Professor at the Polytechnic University of Madrid, an international reference in animal nutrition and a member of the âSumando esfuerzosâ (Joining efforts) working group, whose main objective is to support the swine sector and provide guidance in the face of the definitive withdrawal of zinc oxide.

What are the key points to consider in the post-weaning period to ensure a correct adaptation of the piglets, always prioritizing the control of diarrheal processes?

Increased physical activity (fighting for survival), thermoregulation, stress, and boosting immunity are important factors to consider because they represent a considerable energy expenditure for piglets in the post-weaning period, with the added problem of low feed intake in this problematic phase.

In this regard, the drastic and sudden separation from the mother and littermates, the change of environment, and the mixing of litters create a great deal of stress for the piglet, weakening its defenses and diminishing its ability to adapt. If we add to this the lack of regulation of body temperature, we find ourselves with weak animals, unable to defend themselves against more aggressive pen mates.

The expenses caused by stress and the mechanisms of immunity and defense are very important, as the piglet has to dedicate the few nutrients it consumes to âproduceâ acute phase proteins (APP) with higher proteins production in the liver and lower in muscle.

In relation to protein metabolism, it is important to remember that, during the post-weaning period, muscle growth is not a priority for the piglet.

What happens with feed intake in the post-weaning period?

The piglet eats little or nothing in the first hours after weaning, especially if weaning occurs at 21

days of age.

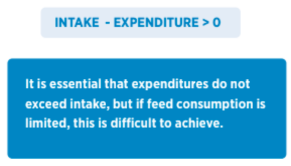

The pigletâs goal at this stage of its life is to ensure that the intake minus the energy and protein expenses necessary for physical activity, such as fighting, thermoregulation (cold), stress (lack of consumption), and immunity (health defense), is not negative. That is:

It is estimated that up to 25-30% of piglets weaned at 21 days of age do not eat anything during the first 20 to 24 hours post-weaning.

If the piglet does not eat, the production of hydrochloric acid and digestive enzymes is reduced, as what is not needed ceases to be a priority.

The problem is not stress itself. What happens is that nature is wise and does not produce digestive enzymes or hydrochloric acid because they require a great deal of energy, and if the animal does not eat, it does not need to be prepared to digest feed and therefore saves energy.

Why produce hydrochloric acid and enzymes if they have nothing to digest at the moment?

After the increase in muscle mass, the growth of intestinal villi is where the post-weaning piglet dedicates more energy and nutrients to improve the absorption of any available nutrients.

If the piglet does not eat and does not produce digestive enzymes, why does it need to improve the absorption of nonexistent nutrients? Hence, the development of the mucosa of the small intestine is reduced.

However, after 20-24 hours without eating, the hungry piglet overeats, bringing more feed than necessary to a digestive system that is not prepared, with limited production of hydrochloric acid and enzymes, and intestinal villi in the process of deterioration.

However, after 20-24 hours without eating, the hungry piglet overeats, bringing more feed than necessary to a digestive system that is not prepared, with limited production of hydrochloric acid and enzymes, and intestinal villi in the process of deterioration.

In this situation, part of the ingested feed passes undigested to the large intestine, where we will have problems with the excessive proliferation of pathogenic microbiota, such as clostridia and coliforms.

What are the key points regarding post-weaning feeding?

It is important to ensure high consumption by the piglet prior to weaning, consumption that should

be maintained during the post-weaning period, as long as the piglet remains healthy and without

diarrhea.

In the presence of digestive processes, the production objective changes:

An important aspect to consider is to avoid excess nutrients in the large intestine in order to reduce the incidence of abnormal fermentations.

In this regard, it is worth establishing a clear difference between the two key components of

feed: carbohydrates and proteins.

In general, it is estimated that more fermentations in the cecum lead to more digestive problems, which is not necessarily true.

The fermentation of carbohydrates is probably less harmful (not necessarily beneficial) than we have always believed.

The fermentation of carbohydrates is probably less harmful (not necessarily beneficial) than we have always believed.

The fermentation of proteins, with the consequent production of ammonia, indoles, and other nitrogenous waste products, is probably more problematic than expected.

The fermentation of proteins, with the consequent production of ammonia, indoles, and other nitrogenous waste products, is probably more problematic than expected.

On the other hand, fermentation of the nitrogenous fraction leads to alkalinization of the tissues and disproportionate growth of Clostridium sp. and other pathogenic microorganisms in the large intestine.

In case of enteric problems, we should be much more concerned about an excess of protein than an excess of carbohydrates.

In any case, the main objective should always be to maintain an adequate health level of the pigletâs gastrointestinal tract in the post-weaning period.

What are the feeding objectives of piglets weighing 7 to 10 kg?

Before the prohibition of the use of pharmacological doses of zinc oxide, the objective was clear: to achieve good daily weight gains and exceptional feed conversion rates at minimum cost.

In order to achieve this goal, early weaning (<22 days of age) predominated with mortality rates and delayed piglets of less than 4-5% during the pre-fattening period, thanks to the preventive use of antibiotics and therapeutic doses of zinc oxide (ZnO).

Today, in the absence of this safety net, the incidence of diarrhea and mortality during the first 10 to 15 days post-weaning has notably increased. As a consequence, mortality and the percentage of delayed piglets initially increase.

For this reason, later weanings are sought to obtain piglets that are physiologically more mature and can more easily overcome the post-weaning stress.

For this reason, later weanings are sought to obtain piglets that are physiologically more mature and can more easily overcome the post-weaning stress.

Based on these changes and our own learning, the problem can and should be overcome, as we are seeing in countries in our economic environment, such as the Netherlands.

In summary, we need to learn how to manage piglets without zinc oxide and without antibiotics, and for this, we already have examples and practical technologies to follow.

What is the ultimate goal?

The ultimate goal of the process is clear, and I can confirm that it can be done: to achieve pigs with live weights and slaughter conversion rates similar with or without zinc oxide.

![]()

But the necessary changes to produce healthy piglets in the absence of ZnO require time and dedication, and above all, following a logical course of action.

The performance losses, mainly due to low weights and high conversion rates, that we will

have during the early post-weaning phases without using zinc oxide can be recovered during the fattening phase, with pigs that will respond much better to any medication, if necessary.

This makes sense, as at the end of its productive cycle, a healthy pig gains over 1 kg/day, while in the post-weaning period, daily growth barely reaches 300-350 g/day. Therefore, a healthy animal recovers in a few days any potential losses it could have had from not using zinc oxide (always in the absence of diarrhea).

What are the strategies for weaning without zinc oxide?

- Reduce stressful situations to the minimum, ensuring that the piglet does not suffer from anything and is seen attentive and happy. Just like with humans, a stressed piglet is not thinking about eating.

- Only wean mature piglets with at least 26-28 days of age and an average live weight of around 7 kg. Without the use of ZnO, we need mature piglets.

- Ensure good litter uniformity. When we have 16 piglets/litter, as is common today, we are not going to have uniform weights, so we must wean them at an older age and improve animal handling and care.

- Pay attention to feed grinding. Very fine grinding improves feed digestibility but harms the pigletâs digestive physiology to some extent. We have to choose!

- Ensure that piglets leave the farrowing room knowing how to eat. This condition is probably the main reason for success or failure.

- Control the presentation and quality of ingredients and feeds, as well as the manufacturing processes.

- Avoid long storage in the factory of expensive, high-value-added ingredients.

How to approach intestinal health without zinc oxide?

The level of crude protein in the feed is important.

Letâs remember that protein that is digested does not cause diarrhea! The problem comes from the amount of protein in the feed that is not digested.

Excess protein cannot be stored. The hydrocarbon fraction of it is transformed into fat, via the Krebs cycle, but the nitrogen fraction gives rise to variable amounts of ammonia, amines, phenols, and indoles that alkalize the tissues and damage the pigletâs physiology before being eliminated.

In particular, the catabolism of branched-chain acids produces more toxic products that are probably the most dangerous.

The low production of hydrochloric acid by the piglet is a problem to be solved because, in case of deficiency, pepsinogen is not activated, and protein digestibility is reduced at the stomach level.

An additional problem is that exogenous phytases, commonly used in pig feeding, are not able to degrade phytates, an important antinutritional factor, if they are not solubilized.

In case of high pH in the proximal digestive tract, as occurs in the post-weaning period, the activity of phytases and, therefore, the availability of phosphorus may be compromised.

Therefore, it is important to keep the levels of Ca and crude protein in post-weaning feeds under control.

Traditionally, fiber has been considered a diluent and an antinutritional factor in early-

age feeds.

The generally accepted philosophy was that the less fiber, the better, as excess fiber reduced consumption and affected the digestibility and growth of the animals.

![]() It was believed that an excess of fiber favored the colonization of the gastrointestinal tract by pathogenic microorganisms and, therefore, increased the incidence of post- weaning diarrhea.

It was believed that an excess of fiber favored the colonization of the gastrointestinal tract by pathogenic microorganisms and, therefore, increased the incidence of post- weaning diarrhea.

However, this belief is not necessarily correct and depends largely on the hygiene, health, and age of the animal, as well as the source and level of fiber in the feed.

When we talk about piglets with digestive problems, we are mainly referring to the benefit of supplying insoluble fiber.

Insoluble fiber is poorly fermentable and, therefore, does not produce volatile fatty acids that can be absorbed into the digestive mucosa and serve as energy for damaged colonocytes.

However, this insoluble fiber affects intestinal motility, increasing the speed of digesta transit in the small intestine and reducing the capacity of bacterial adherence to the digestive mucosa.

The growth of the microbial flora requires:

- A high digestive content as a substrate.

- A limited transit speed to have time to ferment the digesta, grow, and multiply.

Another important issue, which is often overlooked, is the importance of the macromineral fraction of feeds, particularly calcium, on the digestive physiology and growth of the piglet.

- Calcium is necessary for harmonious growth of bone tissue. However, it affects the palatability of the feed and interacts with phosphorus absorption, increases pH due to its buffering capacity, reduces the activity of pepsin and phytases, causes dysbiosis in the gastrointestinal tract, and occupies space in the formula.

- Additionally, the negative effect of an excess of calcium on the integrity of the digestive

mucosa has recently been studied, with an increase in the incidence of processes caused

by Clostridium perfringens.

Calcium is probably the most expensive nutrient, despite its low price, in piglet feed.

To conclude, regarding antibiotics and additives:

There are no additives that can replace zinc oxide, but there are some that can help the piglet defend itself against stress and problematic environmental situations.

While it is true that antibiotics reduce the growth of pathogens and, therefore, control digestive problems, their use also reduces the diversity of the intestinal microbiota, causing an imbalance and an increase in pathogen resistance.

Additives have a lesser effect on the growth of pathogens than antibiotics, but they promote the diversity of the intestinal microbiota and allow for a greater subsequent response, when necessary, to curative antibiotic treatments.